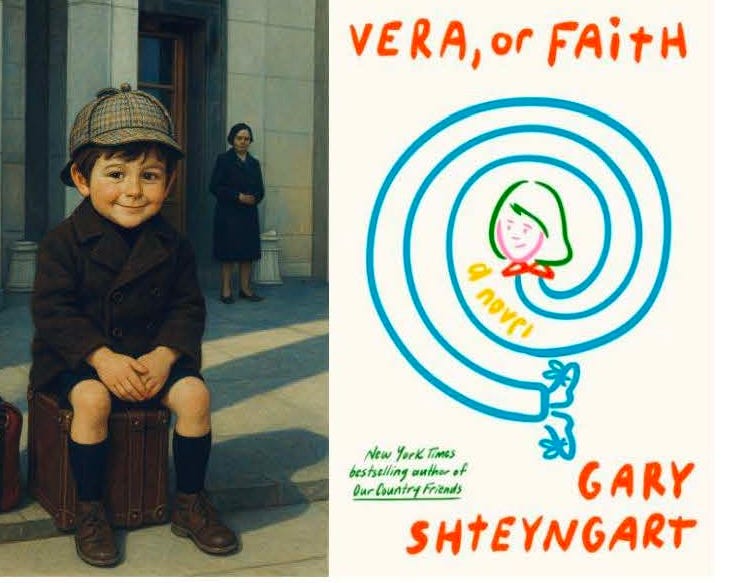

Dispatch No. 9: Larik Meets Vera

or, Taking Unruffled Cheer with a Grain of Faith

What happens when two children from opposite sides of the Cold War take a literary DNA test and discover a faint ancestral link, far closer than third cousins twice removed, yet just as star-crossed?

Larik meets Vera — against all odds but, naturally, thanks to bilingual mischief, misplaced fathers, and uncanny coincidences that refuse to be canny.

Larik’s sister has just magically turned up in Manhattan. Her name is Vera — and she’s Korean. Except for the name. Well, half. The other half is Russian. Through her daddy, who is not exactly Russian. And, incidentally, not Larik’s daddy.

Larik’s daddy, in fact, isn’t Russian at all — he’s British. Larik’s mum is Russian. But you get the idea: cultural identity is a labyrinth — just like families. And that’s what makes Vera and Larik literary siblings. Through daddies, who are unchangingly alike.

Oh, those daddies! Those intellectuals — wrapped in affluence, irony, and guilt, sealed inside an enigma.

And mums — or moms? They’re always there, even when they’re not anymore: taken away by illness, or run over by an imaginary but oh-so-scary arms race. Vera’s mum is there as a weighted blanket she wraps herself in at night, a shield against the exhausting anxiety. Larik’s — as her dressing gown he hides under from the nuclear mushroom, during the “tooth-wrenching” twenty minutes she’s gone to buy his medicine at the chemist’s.

And yes, Larik grows up during the Cold War. Think that war’s gotten a bit warmer recently? Read the news — or Vera! It’s amazing how quickly the atmosphere of a spy drama thickens whenever the Russians appear. Or the British. Or the Koreans.

Vera wishes she could have learned Korean — to reconnect with her Korean self — or at least made better use of her Russian classes, to be able to decipher her daddy’s subversion. Larik, meanwhile, masters English better than most English “childrens” — or so he claims. So well, in fact, that he later returns to Russia for a summer course in “Russian as a Foreign Language.” That’s when his Babushka facepalms with her sacramental, “Imagine that!”

Larik writes through his five-to-fifteen-year-old self; Shteyngart’s Vera speaks as a ten-year-old girl — which she is. In both worlds, words go astray — mistranslated, misheard, or misunderstood — and that’s where the real stories begin.

Vera struggles at an elite New York City school, feeling misunderstood and lonely — the perpetual oddball. Look at Larik at Huxley Boarding School (the name speaks for itself — thank goodness it isn’t Orwell Grove, that hothouse for future PMs).

Vera is good with words and keeps a diary of new ones to learn; she wins the sophisticated debates. Larik is more of a field researcher — taking chances, running experiments, never discouraged by peer taunting; and when the arguments end, he can fire a wad of blotting paper through a tube — an unanswerable rebuttal.

Both kids are self-propelled stars of their personal road-slash-coming-of-age dramas: seemingly motionless, yet full of agency. Vera rides in a self-driving car in pursuit of her Korean identity and her long-lost maternal grandparents. Larik rides in his sleep, wrapped in his mother’s embrace, inside the trunk of a car (or am I revealing too much classified information?) as the family escapes west, through the gates of the British Embassy in Moscow.

Both Larik and Vera navigate the impossible syntax of belonging — switching tongues, decoding parents, mistranslating love. What begins as emotional-cum-linguistic confusion becomes their way of surviving the world.

Fittingly, Vera was published on July 8, 2025 — the same day Larik found his own home in print. As important “stakeholders” of the future (though Larik flirts with vegetarianism — being a Taurus, he strongly opposes cannibalism), some children are simply destined to meet across time zones and generations.

Coincidence? Don’t think so — as any Russian would tell you, arching an eyebrow.

And do you believe in… fairies?